Fairs

Thanks to the fantastic breadth of the world's fair collections at Hagley Museum and Library and the Henry Madden Library, Fresno, there are more than 200 fairs represented in this resource. To browse the full list, please see the Fairs Directory.

The fairs detailed below are the twelve fairs chosen to serve as case studies. These represent some of the most prominent and influential expositions in history, and have been selected based on the advice of our Editorial Board and the existence of appropriate archival collections. The aim of each case study is to offer a comprehensive insight into the fair, from the earliest planning stages to the legacy it leaves behind, and to represent multiple perspectives including the official, the corporate and the personal. Each case study also includes a range of material types to support this.

1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, London

![]() Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1851 Great Exhibition.

Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1851 Great Exhibition.

The Great Exhibition is arguably the most famous of the World’s Fairs, marking the birth of the international exposition phenomenon which continues to this day. Whilst national exhibitions of trade and industry had taken place since the 18th century, the Great Exhibition was the first to do so on an international scale, and as a result it is considered to be the first World’s Fair. Organised chiefly by Henry Cole and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the exhibition became an indomitable symbol of the British Empire’s global influence and power. It was also a social, political, and economic vehicle designed to celebrate technological innovations, to promote modernisation, to increase trade relations with foreign countries, and to educate the general public.

The exhibition took place in London’s Hyde Park under the sparkling roof of one building – the iconic and colossal Crystal Palace which was made almost entirely of glass and covered nearly 19 acres. The building was designed by the architect Joseph Paxton and it involved the largest amount of glass ever used in a building at the time, thanks to the innovative cast plate glass method of production developed in 1848. The building hosted 13,000 exhibits; 7,000 British displays occupied the western side and participating foreign countries occupied the eastern half. Some of the most innovative exhibits included William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone’s electric telegraphs and John and Jacob Brett’s submarine telegraph machine for communication across seas. Other famous exhibits include the Koh-i-Noor diamond (the largest known diamond in the world at this time), Samuel Colt’s firearms prototypes, and the Folkestone locomotive engine. The exhibition is also notable for including the first large-scale implementation of public toilets which cost a penny to use and consequently coined the saying “to spend a penny”.

The exhibition was opened by Queen Victoria on 1st May 1851 and continued until 15th October 1851, attracting 6 million visitors (Britain’s population at this time was approximately 18 million), with the highest recorded daily attendance reaching 109,915. It generated a profit of £186,000 (the equivalent of approximately £17,770,000 in today’s money) which the Royal Commission for the Exhibition used to establish an area in London’s South Kensington dedicated to education in the arts and sciences. The resulting institutions in this area include the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum, the Natural History Museum, the Albert Hall, and Imperial College London. Whilst the Crystal Palace itself was destroyed by a fire in 1936, the legacy of the Great Exhibition can be found in this continuing endeavour for education, as well as in every one of the international expositions that followed in its wake.

1876 Centennial International Exhibition, Philadelphia

![]() Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition.

Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition.

Held in celebration of the 100th anniversary of American Independence, the 1876 Centennial Exposition was the first definitive world’s fair in America, and for the relatively new, divergent and dynamic country, it became a way to consolidate and promote the country’s national identity. The fair’s formal name was the International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures and Products of the Soil and Mine and it boasts a number of firsts for the American exposition tradition.

A Centennial Commission headed by General Joseph R. Hawley was set up by Congress to oversee the running of the fair and in order to manage the fair’s finances a Centennial Board of Finance was also established. 285 acres of Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park were occupied by the fair site, the design of which was entrusted to architect Hermann J. Schwarzmann. His design involved creating a number of feature buildings such as the Memorial Hall, the Agricultural Hall and the Machinery Hall, and surrounding these with various smaller pavilions (rather than exhibiting everything under one roof), which became the typical format for all subsequent world’s fairs.

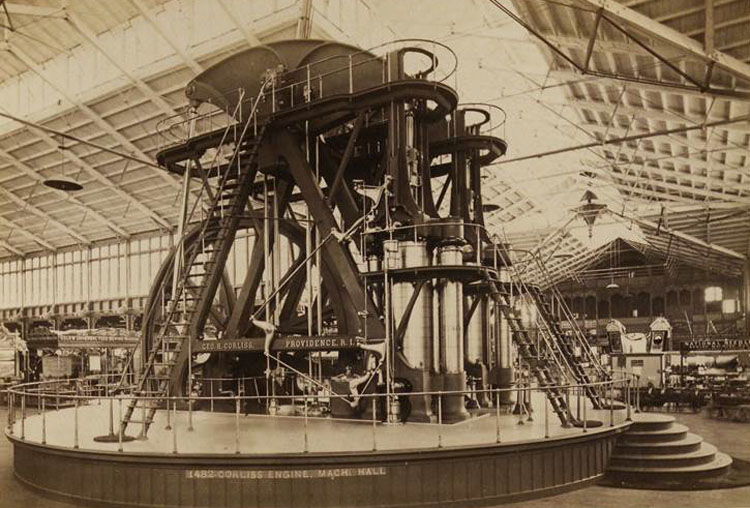

The fair opened on May 10th 1876 with an opening ceremony which included US President Ulysses S. Grant and Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro II powering up George Corliss’s 700-ton Giant Corliss Engine. The machine was the most popular exhibit at the fair and it supplied power to the rest of the Machinery Hall’s exhibited inventions, allowing visitors to witness the machines in action. Some of the key inventions and products first introduced to the public at the Centennial Exhibition include typewriters, a mechanical calculator, Bell’s first telephone, Heinz Ketchup, bananas and popcorn. Other highly popular exhibits included the Declaration of Independence, the Liberty Bell, and the arm, hand and torch of Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi’s unfinished Statue of Liberty. Whilst progress in equal rights was made with the first Women’s Building to feature at a World’s Fair, racial equality remained a contested issue and African Americans were poorly represented at the fair, with African American women (who had helped to raise money for the fair) being prevented from participating in the Women’s Building.

Despite a summer heat wave impacting attendance, when the fair closed on November 10th 1876 it had received nearly 10 million visitors. Unfortunately, it still made a loss of $1.5 million, but with 37 foreign countries having participated in the fair, America had more importantly made its young but distinct voice heard across the Atlantic.

Australian International Exhibitions: 1879/80 Sydney, 1880/81 Melbourne, 1888/89 Melbourne

![]() Click here to explore the documents relating to the Australian fairs.

Click here to explore the documents relating to the Australian fairs.

Within a ten-year period from 1879 to 1889, Australia hosted three international exhibitions, all of which had an irrevocable influence on the cultural, social and economic progress of the colonies that had been claimed by the British Empire a century earlier. Inspired by previous international exhibitions, these fairs gave Australia’s colonies the opportunity to demonstrate their growth since the early days of penal settlements, to present themselves as cornerstones of the British Empire and to help build a national sense of identity that would later be affirmed with the Federation of Australia in 1901.

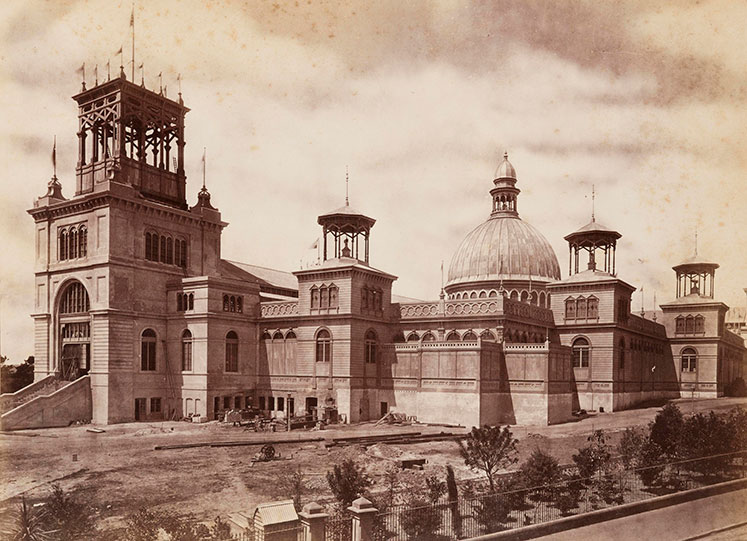

Sydney’s 1879 International Exhibition was the first international exhibition held south of the equator, and it was attended by over 1 million people from all over the world. Overlooking Sydney Harbour, the focal point of the fair was the magnificent Garden Palace, designed by architect James Barnet. This building housed many of the fair’s 14,000 exhibits which were organised into national and colonial courts and included displays from Fiji, India, Italy and Tasmania. Accompanying the Garden Palace was an Agricultural Hall, a Machinery Hall and an Art Gallery which featured European works of art never before displayed in the Australian colonies. Music dominated the fair’s entertainment with classical concerts, brass bands, recitals and choirs, and music was composed especially for the exhibition. Whilst the fair closed officially on 20th April 1880, it provided the colony of New South Wales (NSW) with new cultural and educational institutions, improved international trade relations, and cultivated a strong international presence.

Sydney’s 1879 International Exhibition was the first international exhibition held south of the equator, and it was attended by over 1 million people from all over the world. Overlooking Sydney Harbour, the focal point of the fair was the magnificent Garden Palace, designed by architect James Barnet. This building housed many of the fair’s 14,000 exhibits which were organised into national and colonial courts and included displays from Fiji, India, Italy and Tasmania. Accompanying the Garden Palace was an Agricultural Hall, a Machinery Hall and an Art Gallery which featured European works of art never before displayed in the Australian colonies. Music dominated the fair’s entertainment with classical concerts, brass bands, recitals and choirs, and music was composed especially for the exhibition. Whilst the fair closed officially on 20th April 1880, it provided the colony of New South Wales (NSW) with new cultural and educational institutions, improved international trade relations, and cultivated a strong international presence.

Swiftly following Sydney’s success, the BIE-recognised 1880/81 Melbourne International Exhibition took place in the city’s Carlton Gardens, where the celebrated Exhibition Building (designed by Joseph Reed) with its Florence Cathedral replica dome was situated. Headed by Victoria magnate Sir William John Clarke, the fair included exhibits from 33 countries with the United States displaying innovative technologies such as the typewriter, lawn mower, and electric lighting. Machinery and gold mined in the colony were the key attractions in Victoria’s exhibit, whilst Germany’s display included musical instruments, porcelain and beer, and India’s exhibit offered visitors samples of exotic teas. Attracting almost 1.5 million visitors, the exhibition’s popularity anticipated the great land boom of the 1880s, during which Melbourne became one of the largest cities in the British Empire. The Exhibition Hall, now known as the Royal Exhibition Hall, remains a pivotal part of Melbourne’s cityscape and culture to this day, and was awarded World Heritage status in 2004.

Seven years later, Melbourne was called upon to host NSW’s 1888/89 Centennial International Exhibition to mark the centennial of the founding of NSW by Governor Arthur Philip. Economic difficulties and the lack of a suitable exhibition site (Sydney’s Garden Palace having sadly been destroyed by fire in 1882) led to Victoria’s hosting of the event on NSW’s behalf. Melbourne’s Exhibition Hall, updated with newly built annexes, new interior decorations, and electric lighting, became the hub of the Centennial Exhibition. Politician Sir James McBain presided over the event which included over 90 participating countries and a 38-acre fair site. Victoria’s substantial exhibit space featured examples of industrial machinery, whilst France’s exhibit featured a replica model of the Eiffel Tower covered with champagne bottles, and the US demonstrated its latest inventions from Thomas Edison and the Singer Company. Classical concerts conducted by Frederic Cowen proved a highlight of the fair, as did various sideshow attractions, including a shooting gallery and acrobatic performances, and an electric railway (a prototype for the first electric tramway in Australia). The Centennial International Exhibition went on to become one of the most extravagant (and costliest) events held in Australia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, attracting over 2 million people.

1889 Exposition Universelle, Paris

![]() Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1889 Exposition Universelle.

Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1889 Exposition Universelle.

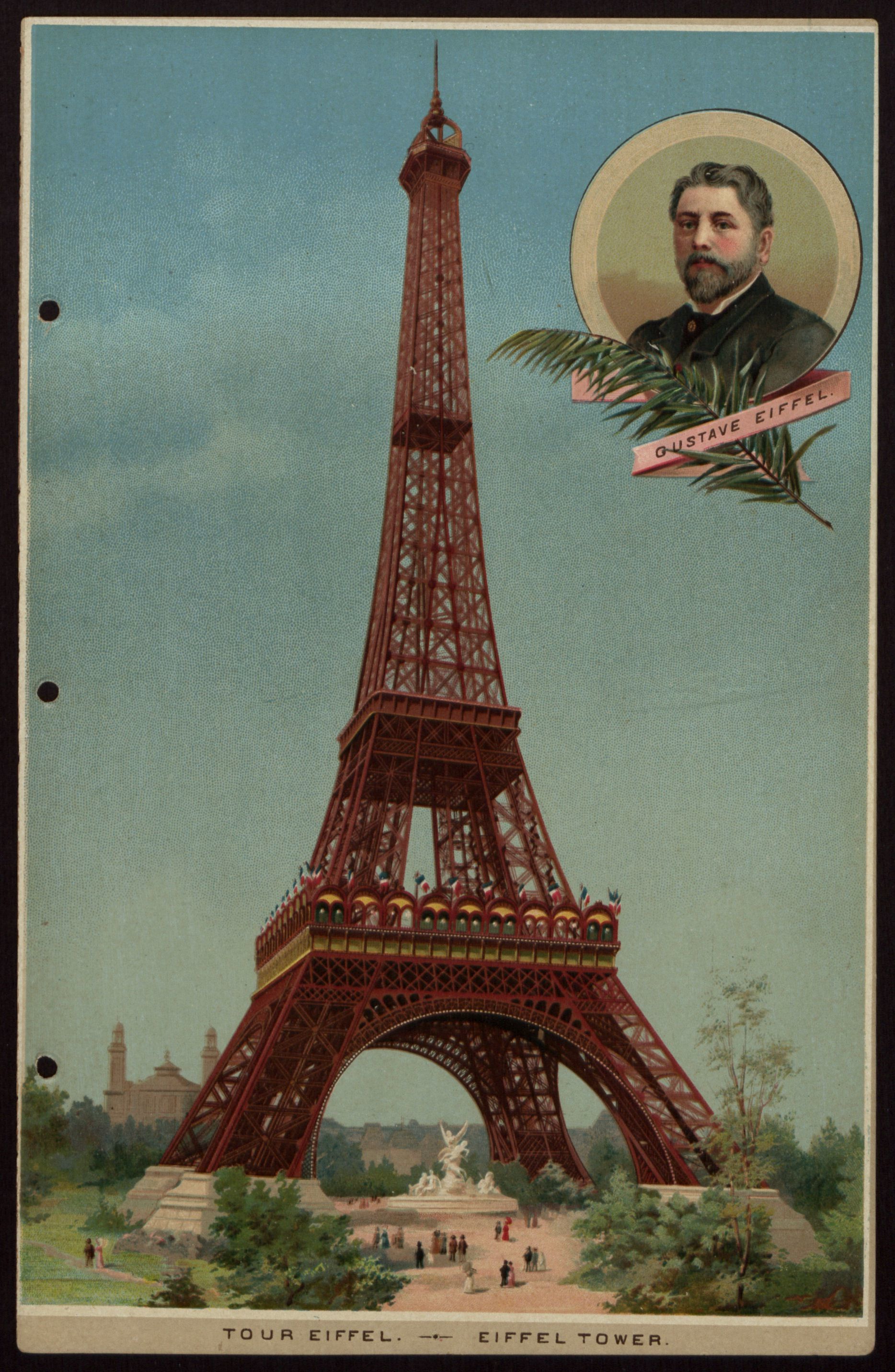

The Exposition Universelle took place between 6th May and 6th November 1889 and is perhaps France’s most significant fair having gifted the city with Gustave Eiffel’s Eiffel Tower, one of the most famous national symbols in the world. The year of the fair was also the centennial anniversary of the French Revolution but fair officials were keen to keep the two events separate in order to encourage monarchist European countries to participate. The fair was instead marked as a celebration of the Third Republic which governed the country at the time, and this was reflected in the range of exhibits (1,171 in total) that focused on social economy, including The History of Work and The Palace of Hygiene.

The fair site encompassed the Champs-de-Mars, Palais du Trocadéro, Quai d’Orsay, and Esplanade des Invalides and featured 61,722 exhibitors. It was visited by over 32 million people and was hugely successful, making a profit of 8 million francs. As well as the Eiffel Tower, it boasted a number of architecturally stunning exhibits including the innovative Galeries des Machines, designed by Ferdinand Dutert and constructed by Victor Contamin, and the expansive History of Human Habitation exhibit which was designed by Charles Garnier.

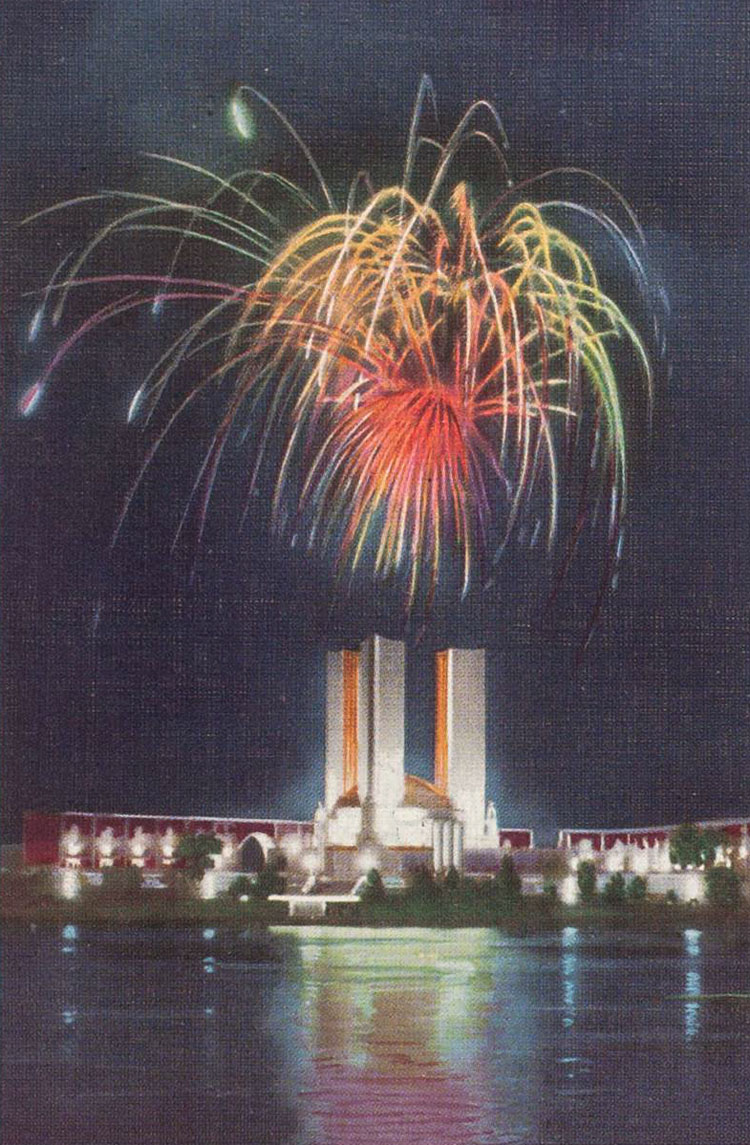

In contrast to Paris’s previous fairs, the Exposition Universelle focused not only on showcasing new products and inventions but also on how such technological developments could be used to evoke wonder. For example, the Galeries des Machines included a suspended moving platform above the machinery which was used to transport visitors across the exhibit whilst offering them an excellent view of the mechanical displays. A sense of magic was created at night by the fair’s illuminations which included frequent firework displays and a gleaming Eiffel Tower lit up by masses of colorful electric bulbs. As a result of its commitment to inspiring awe through spectacle, illusion and illumination, Paris at this time became known as the “cité féérique” (fairy tale city).

1893 World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago

![]() Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago

Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago

During the 1880’s cities in America were embroiled in a battle to be crowned the host of the World’s Columbian Exposition. This was the fair which in 1892 would commemorate Christopher Columbus’s discovery of the New World and would symbolise America’s increasing status and power. The most significant contenders were New York and Chicago and it was only after Chicago won a congressional vote that it could claim the honour. Due to these complications, the fair arrived a year later than planned but it proved to be an incredible success which not only elevated America’s reputation but which also allowed Chicago to take its place alongside the East coast’s New York, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C., as one of the most important cities in America.

Unlike previous American fairs, it was organised by two separate bodies: the government’s National Commission and the funds based Chicago Corporation which resulted in the fair becoming much more of a commercial enterprise, complete with a very effective publicity department. Many of these initiatives greatly influenced the running of future American fairs. The site selected for the fair was the 600-acre Jackson Park and Daniel H. Burnham, John W. Root and Frederick Law Olmsted oversaw its planning. Burnham and Charles B. Atwood were also responsible for the fair’s white, neo-classical architecture which earned the fair its “White City” nickname and went on to be a huge influence on American architecture. Atwood’s Palace of Fine Arts, now known as the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry, is the fair’s only surviving building but arguably the most memorable structure was a distinctly modern innovation by George W. Ferris called the Ferris Wheel: a 264-foot high attraction which could carry approximately 2000 people at a time.

The Columbian Exposition’s exhibits and entertainments were breath-taking in their scope and diversity, with the Palace of Fine Arts alone holding 9,000 paintings. It is notable for its endorsement of a Women’s Building (designed by Sophia G. Hayden) and the organization of influential conferences and congresses involving people such as Woodrow Wilson, Frederick Jackson Turner, and Jane Adams. The fair also marked the development of the hugely successful Midway Plaisance, an area reserved solely for amusement and entertainment, which became an essential part of all subsequent American fairs. The amount of electricity used to illuminate the fairground was unprecedented, and at night the exposition became an incandescent wonderland with the lights reflecting upon the fair’s many white buildings, lagoons and water pools. From its opening on May 1st 1893 to its closure on October 30th 1893, the Columbian Exposition received 21.5 million paid admissions and it is the fair which undoubtedly secured America’s reputation as a significant player in the World’s Fairs tradition.

1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St. Louis

![]() Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition.

Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition.

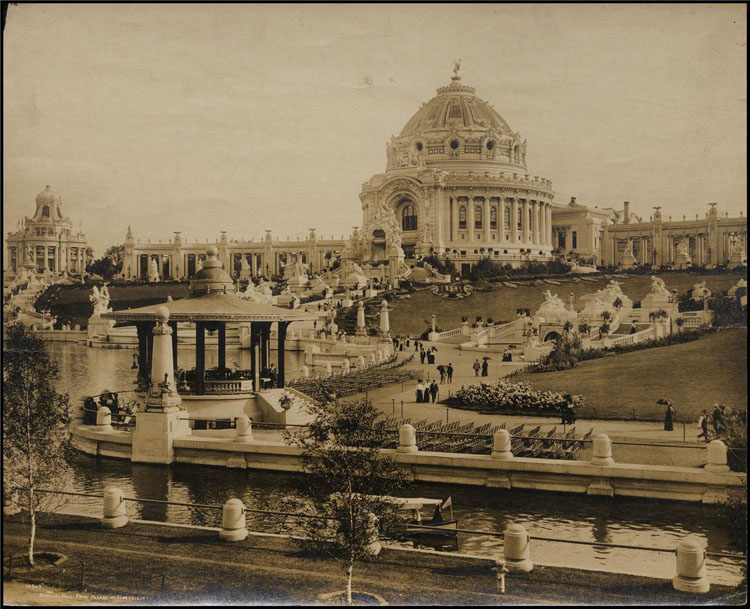

The 1904 St. Louis fair was a celebration of America’s acquisition of the territory of Louisiana in 1803. With a theme based on national expansion, it is unsurprising that it had strong imperialist tones and celebrated white American achievement and colonization. Questions of race surrounded the fair, and continue to hold a place in how it is interpreted. Humanity’s increasing control over the natural world was also explored. On a more local level, many of those who visited the fair remembered it fondly, and it has remained an integral part of the city’s culture and memory.

There were strong similarities between the LPE and the World’s Columbian Exposition. The size, scope and architecture of the fair mirrored that of 1893, while popular exhibits such as the Ferris Wheel made a return. Underlying all of this was a mutual aim for the cities playing host. Like Chicago, St. Louis wanted to improve its poor reputation and demonstrate its standing as a respectable and integral U.S. city.

There were strong similarities between the LPE and the World’s Columbian Exposition. The size, scope and architecture of the fair mirrored that of 1893, while popular exhibits such as the Ferris Wheel made a return. Underlying all of this was a mutual aim for the cities playing host. Like Chicago, St. Louis wanted to improve its poor reputation and demonstrate its standing as a respectable and integral U.S. city.

At 1,272 acres, the fair site at Forest Park was the largest ever. Preparing the site involved re-routing the Des Peres River, creating a new water system for the whole city, draining and molding a natural lake into a new artificial basin, and laying out an accessible array of buildings that came together to form an elegant skyline. The buildings, frequently designed in the Beaux-arts style, fanned out from the Festival Hall and became known as the “Ivory City”. In front of Festival Hall flowed E. L. Masqueray’s Cascades; these waters were lit in rainbow colors and led to the Grand Basin.

The usual mix of artistic and industrial exhibits filled the main site, while popular entertainment displays included Jim Key the educated horse and performances by Native American tribes. The last of these was just one of the exhibits that drew attention to white American national expansion and colonialism. The most significant was a 47-acre site dedicated to the Philippines, which became a US protectorate in 1898. The exhibit cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and featured recreated villages and traditional cultural displays by Filipino tribes. Large numbers of visitors were fascinated by the native people and their culture, which was depicted as inferior to its western counterpart. The message given out by this exhibit was clear – America had an imperial mission in the world comparable to that of the European powers; it too could colonize and “civilize” as part of its manifest destiny.

20 million people visited the fair. Its infrastructure improved the city and its place in popular culture was secured by the 1944 film Meet Me in St. Louis. Even as its host city went into something of a decline, the memory of the fair remained strong.

1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition, San Francisco

![]() Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition.

Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition.

The Panama Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) was a celebration of the completion of the Panama Canal on August 15th 1914 which was a momentous event for the American West, creating a vital international trade route and, with it, a  myriad of commercial and economic opportunities. It was also an opportunity to demonstrate the city of San Francisco’s resilience and incredible progress following the devastating events of 1906. The latter message became particularly poignant during the course of the fair with the shadow of World War I spreading across the globe.

myriad of commercial and economic opportunities. It was also an opportunity to demonstrate the city of San Francisco’s resilience and incredible progress following the devastating events of 1906. The latter message became particularly poignant during the course of the fair with the shadow of World War I spreading across the globe.

The fair took place next to Fort Mason on the northern shore of San Francisco Bay and was largely funded by municipal and state bonds and from the city’s commercial industries. It was designed by a number of talented architects, engineers and artists, including architect George W. Kelham and artist Jules Guerin who was the fair’s Director of Color. The plan of the site consisted of three main courts: the Court of the Universe, the Court of Ages (later called the Court of Abundance) and the Court of the Four Seasons, with each court being formed by pavilions. With an abundance of domes adorning its buildings, the fair site became known as the “City of Domes”, the most impressive of which was a vast glass dome atop the Palace of Horticulture. The fair site’s classical architecture is best represented in its only remaining building, Bernard Maybeck’s beautiful Palace of Fine Arts, but the centrepiece of the fair was the 432-foot high Tower of Jewels, covered in murals, statues and over 100,000 mirror-backed glass jewels. The PPIE’s innovative use of searchlights and projectors for illumination around the fair site set the stage for the fair’s dazzling constructions.

The celebratory mood of the fair was also harnessed in the exhibits themselves. Amongst the most popular exhibits were the Ford Company’s working factory (capable of producing eighteen Model T’s in a day), James Earle Fraser’s sculpture ‘The End of the Trail’, and a 5-acre working model of the Panama Canal – all symbolic of American progress. Exhibitors made use of developments in film technology to screen moving pictures and Keystone even produced a comedy-documentary film set at the fair starring Roscoe Arbuckle and Mabel Normand. An array of special events also took place at the fair, including concerts, sporting events and air shows. When the fair closed on December 4th 1915, 28 foreign countries and 32 states and territories had participated. It received more than 18,000,000 paid admissions and made an incredible profit of $2,401,911.

1933/34 Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago

Chicago’s Century of Progress Exposition was proposed during the 1920’s as a way to mark the centennial of the founding of the city and all that it had achieved. The fair’s key focus was to celebrate scientific progress and to promote its integral role in creating a modernized, efficient, and better future. This proved to be a particularly poignant endeavour in light of the incredible hardships suffered by the people of the United States during the years of the Great Depression, and as a result the fair also became an important symbol of hope and optimism.

Taking place on the shore of Lake Michigan, one of the most memorable elements of the fair was the architecture and Daniel H. Burnham Jr, Louis Skidmore and Arthur Brown Jr were amongst the talented people involved in the fair’s Architectural Commission. The buildings became particularly famous for their rejection of classical features to make way for the modernist and art-deco style which, fortunately, was also highly economical. This bold, angular, geometric style was epitomised in the design for the Federal Building, its three imposing towers creating a powerful modern symbol that adorned the fair’s publicity. The Hall of Science building was equally striking with its Carillon Tower, and the innovative Travel and Transport Building was enclosed by a height-adjustable suspended dome.

In contrast to earlier fairs, the Century of Progress Exposition offered free exhibit space to corporations and the General Motors and Ford Motor Company exhibits were amongst the fair’s most popular exhibits, helping to fuse the themes of modernisation and American consumer culture. The Sky-Ride, a 628-foot high cable-car connecting the fair site’s two lagoons, was equally popular and became the divisive focal point of the fair, whilst the Midway’s entertainment was dominated by Sally Rand’s infamous nude fan dance for the Streets of Paris show. With such delights on offer the exposition was hugely successful, attracting nearly 40 million visitors during its two seasons and despite taking place during an economically devastating period for the US, it even made a profit.

1939/40 New York World's Fair, New York

![]() Click here to explore the documents relating to the1939/40 New York World's Fair.

Click here to explore the documents relating to the1939/40 New York World's Fair.

The 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair opening day coincided with the 150th anniversary of the inauguration of George Washington and defiantly affirmed the spirit of democracy whilst Europe was being increasingly dominated by totalitarian regimes. The theme of the fair for the first season was ‘Building the World of Tomorrow with the Tools of Today’; for the second it was ‘For Peace and Freedom’, and in the wake of the Great Depression and the imminent outbreak of war, a sense of determination and optimism for the future pervaded the exhibits.  The fair ran for two seasons from 30th April to 31st October 1939, and 11th May to 27th October 1940 and took place in Queens at a site formerly known as “Corona Dumps” before its transformation into Flushing Meadows. It hosted 1,500 exhibitors with 58 nations in participation but the Trylon and Perisphere, two of the most iconic buildings in World’s Fairs history, represented the physical and thematic centre of the fair. Contained within the Perisphere was Henry Dreyfuss’s hugely popular diorama Democracity, a utopian vision of urban and suburban living in the year 2039. As well as social and economic progress, the fair also provided an insight into technological advancements with the American Telephone and Telegraph Company’s Voder and Westinghouse’s Electro and Sparko. Westinghouse also created a time capsule for the fair which contains various items such as a RKO newsreel, a dictionary and a packet of Camel cigarettes. It is buried on the fair site, intended for opening in 6939.

The fair ran for two seasons from 30th April to 31st October 1939, and 11th May to 27th October 1940 and took place in Queens at a site formerly known as “Corona Dumps” before its transformation into Flushing Meadows. It hosted 1,500 exhibitors with 58 nations in participation but the Trylon and Perisphere, two of the most iconic buildings in World’s Fairs history, represented the physical and thematic centre of the fair. Contained within the Perisphere was Henry Dreyfuss’s hugely popular diorama Democracity, a utopian vision of urban and suburban living in the year 2039. As well as social and economic progress, the fair also provided an insight into technological advancements with the American Telephone and Telegraph Company’s Voder and Westinghouse’s Electro and Sparko. Westinghouse also created a time capsule for the fair which contains various items such as a RKO newsreel, a dictionary and a packet of Camel cigarettes. It is buried on the fair site, intended for opening in 6939.

Whilst looking to the future, the New York World’s Fair also ensured its visitors were enjoying the present and an extensive and varied selection of entertainments were provided. This included amusement rides such as the Parachute Jump, and shows such as Billy Rose’s Aquacade or the more risqué Crystal Lassies designed by Norman Bell Geddes (who also designed the fair’s hugely popular General Motors Futurama exhibit). Despite attracting 44 million visitors, the fair failed to make a profit but it remains one of the most iconic and talked about expositions in history.

1967 Expo '67, Montreal

![]() Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1967 Expo '67.

Click here to explore the documents relating to the 1967 Expo '67.

Expo '67 took place from 28th April to 28th October 1967, coinciding with the centennial commemoration of the Canadian Confederation. The fair was carefully structured around the main theme ‘Man and his World’ inspired by Antoine Saint-Exupery’s 1939 memoir Terre des Hommes, and it was organized by sub-themes such as ‘Man and the Community’, ‘Man the Explorer’, ‘Man the Producer’, and ‘Man the Creator’. The exhibits were imbued with a futuristic and utopian sense of humanity as a peaceful collective in harmony with the natural world and the ever-advancing world of technology.

The expansive fair site consisted of the Cité-du-Havre, Île Sainte-Hélène, and Île Notre-Dame, all connected by the specially built Expo Express, and at 988.7 acres it is one of the largest exposition sites in history. Around 60 foreign nations participated in the fair and the USSR and US pavilions were amongst the most popular, fuelled as they were by Cold War tensions (the USSR pavilion on Île Notre-Dame sat opposite the US pavilion on the Île Sainte-Hélène). The USSR pavilion celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Russian Revolution and was the fair’s most extravagant exhibit, costing 15 million dollars. The US pavilion’s geodesic dome, designed by Buckminster Fuller, has since become one of the most famous Expo buildings in history and still stands today as Montreal’s Biosphere.

Whilst political tensions bubbled under the surface, Expo '67’s utopian dreams were proudly heralded in modernist visions such as Moshe Safdie’s definitive Habitat 67, which presented a revolutionary example of urban housing, and through the experimental fusion of visual technologies in the Labyrinth pavilion. In fact, Expo '67 became known as “celluloid city” due to its preoccupation with film technologies. The fair was incredibly successful, receiving 54 million visitors and it is firmly cemented as one of the most significant events in Canada’s history.